“As soon as a child is old enough, he should keep his own nature notebook for his enjoyment.

Every day’s walk will give something interesting to add–

three squirrels playing in a tree, a blue jay flying across a field,

a caterpillar crawling up a bush, a snail eating a cabbage leaf,

a spider suddenly dropping from a thread to the ground,

where he found ivy and how it was growing and

what plants were growing with it, and how ivy manages to climb.”

Charlotte Mason in Modern English, volume 1 page 54

Squirrel eating food from the bird feeder

on January 19, 2008.

This is such a lovely quote with all the different natural images that are shared. I'm hoping that by encouraging the girls to keep nature journals that they, too, will have beautiful memories and images to look back upon.

For this week's theme, we focused on birds of prey and scavengers.

We have been learning about hawks, owls, and other birds of prey. Now we're backing up a bit to look at the bigger picture.

The order Falconiformes is a group of about 290 species of birds that contains the diurnal birds of prey. (Diurnal means the birds are active during day and sleep at night.) They live almost everywhere in the world except Antarctica and eastern Polynesia.

Birds of prey, also known as raptors, hunt and feed on other animals. The term "raptor" comes from the Latin word rapere (meaning to seize or take by force). These birds have keen vision that allows them to detect prey during flight, and powerful talons and beaks.

Many species of birds may be considered partly or exclusively predatory. However, in ornithology, the term "bird of prey" applies only to birds of the five families of two orders listed below:

Accipitridae: hawks, eagles, buzzards, harriers, kites and Old World vultures. These birds have very large powerful hooked beaks for tearing flesh from their prey, strong legs, powerful talons and keen eyesight.

Pandionidae: the osprey. This family of fish-eating birds of prey, possessing a very large, powerful hooked beak for tearing flesh from their prey, strong legs, powerful talons, and keen eyesight.

Sagittariidae: the secretarybird.

Falconidae: falcons, caracaras, and forest falcons. These birds differ from hawks, eagles, and kites in that they kill with their beaks instead of their talons.

Cathartidae: New World vultures. (See below for more information about these scavengers.)

All of the birds that have very good eyesight for finding food, strong feet for catching, killing, and/or holding food; and a strong curved beak for tearing flesh.

This owl is at a nature center.

We saw it on January 18, 2013.

The nocturnal birds of prey – the owls – are classified separately as members of two families of the order Strigiformes:

Strigidae: typical owls. The typical owls are small to large solitary nocturnal birds of prey. They have large forward-facing eyes and ears, a hawk-like beak and a conspicuous circle of feathers around each eye called a facial disk.

Tytonidae: barn and bay owls. Barn owls are medium to large owls with large heads and characteristic heart-shaped faces. They have long strong legs with powerful talons.

We saw this owl was at Warner Nature Center

on October 27, 2012

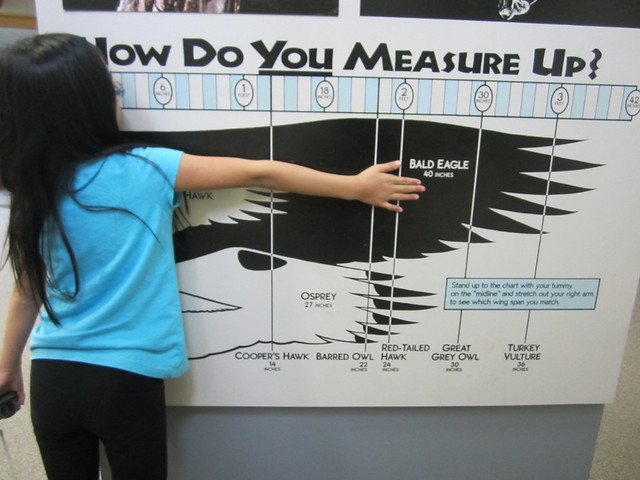

The wing shape of birds of prey vary depending on the type of bird:

As with the wing shape, the wing size varies considerably as well:

Display about the wingspan of various raptors.

This display was at William O'Brien State Park.

We were there on May 26, 2012.

SCAVENGERS

We saw this turkey vulture resting on a fence post

at the end of the road we live on.

This was taken on April 16, 2013.

Vultures are scavenging birds, feeding mostly from carcasses of dead animals without apparent ill effects. It prefers those recently dead, and avoids carcasses that have reached the point of putrefaction. They may feed on plant matter, shoreline vegetation, pumpkin and other crops, live insects and other invertebrates, but this rare.

Bacteria in the food source, which would be pathogenic to other vertebrates, dominate the vulture’s gut flora, and vultures benefit from the bacterial breakdown of carrion tissue.

New World vultures have a good sense of smell, whereas Old World vultures find carcasses exclusively by sight. A particular characteristic of many vultures is a bald head, devoid of feathers.

In Minnesota, we commonly see turkey vultures. This type of vulture, as noted above, is a scavenger and feeds almost exclusively on carrion. It finds its food using its keen eyes and sense of smell, flying low enough to detect the gases produced by the beginnings of the process of decay in dead animals.

In flight, the turkey vulture uses thermals to move through the air and it flaps its wings infrequently.It is a large bird, with a wingspan of 63–72 inches, a length of 24–32 inches, and weighs 1.8 to 5.1 pounds. In flight, the tail is long and slim.

The turkey vulture is gregarious and roosts in large community groups. It breaks away to forage independently during the day. Several hundred vultures may roost communally in groups which sometimes even include black vultures. It prefers to roost on dead, leafless trees, but will also roost on man-made structures such as water or microwave towers.

Lacking a syrinx,which is the vocal organ of birds, its only vocalizations are grunts or low hisses.

Another interesting aspect of its body is that the two front toes of the foot are long and have small webs at their bases. Tracks are large, between 3.7 and 5.5 inches in length and 3.2 and 4.0 inches in width. Both measurements include claw marks.

The feet are flat, relatively weak, and poorly adapted to grasping. In fact, the talons are not designed for grasping, as they are relatively blunt.

The turkey vulture nests in hollow trees, caves, or thickets.

Each year it generally raises two chicks, which it feeds by regurgitation.

It has very few natural predators. In the United States, the vulture receives legal protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

It is found in open and semi-open areas throughout the Americas from southern Canada to Cape Horn. It is a permanent resident in the southern United States, though northern birds may migrate as far south as South America.

The turkey vulture is widespread over open country,pastures, shrublands, grasslands, deserts, subtropical forests, wetlands, and foothills. It is most commonly found in relatively open areas that have nearby woods for nesting. Turkey vultures generally avoid heavily-forested areas.

The turkey vulture forages by smell, an ability that is uncommon in the avian world, often flying low to the ground to pick up the scent of ethyl mercaptan, a gas produced by the beginnings of decay in dead animals.

The olfactory lobe of its brain, responsible for processing smells, is very large compared to that of other animals. This heightened ability to detect odors allows it to search for carrion below the forest canopy.

In areas where others types of vultures and condors live, the turkey vulture sets itself apart from others because it can smell carrion. King vultures, black vultures, and condors, which lack the ability to smell carrion, follow the turkey vulture to carcasses.

The turkey vulture arrives first at the carcass, or with greater yellow-headed vultures or lesser yellow-headed vultures, which also share the ability to smell carrion. It displaces the yellow-headed vultures from carcasses due to its larger size, but is displaced in turn by the king vulture and both types of condor, which make the first cut into the skin of the dead animal.

This allows the smaller, weaker-billed turkey vulture access to food, because it cannot tear the tough hides of larger animals on its own. This is an example of mutual dependence between species.

Like other vultures, the turkey vulture plays an important role in the ecosystem by disposing of carrion which would otherwise be a breeding ground for disease.

Nature Journaling

Both the girls did an entry in their nature journal about birds of prey/scavengers. Sophia focused on birds of prey in general.

Olivia focused on peregrine falcons.

1 comment:

Very interesting! I didn't know Turkey Vultures can't really vocalize. So much interesting information. I like that idea of kids having a nature journal. :)

Post a Comment